From Vice. I hate Vice but the article is a good overview of what’s afoot.

It’s been 23 years since the Berlin Wall was demolished, and now the bulldozers are back. This time, however, no one’s clapping. When word got out that a developer was planning to build a luxury apartment complex right on top of the preserved section of the wall (known as the East Side Gallery), 6,000 people showed up to block the demolition crews, proving that irony is still alive and well in the city that, 23 years earlier, was campaigning to have the wall destroyed.

For a while, the public outcry seemed to work. Protests continued, petitions were signed, local artists spoke out in indignation, and David Hasselhoff even married the wall in protest, which, surprisingly, isn’t the weirdest thing he’s done in his professional career.

The developer in question, Maik Hinkel, was apparently surprised at the response and assured Berliners that he would work with the city’s mayor to find a compromise. But last Wednesday, under the cover of darkness, Hinkel broke his promise and removed eight meters of history forever. The worst part? Hoff never even got a chance to honeymoon 😦

Police guard the East Side Gallery. Photo by Ash Clark

Formerly preserved sections of the wall have been taken down before, but it’s never sparked such a huge reaction. Most of the protesters I spoke to were less concerned with the wall itself than with the super expensive apartments that were replacing it because these days the word on every Berliner’s lips is “gentrification.”

Protesters near the wall. Sign reads: “Berlin is not for sale.” Photo by Nina Hüpen-Bestendonk

It’s no secret that Berlin is changing. Nowadays, on a Sunday morning, the distant thud of the Berghain’s sound system gets drowned out by the nasal chatter of American exchange students drinking lattes in cute, authentic cafés.

And the phrase “Silicon Allee” (Berliner Allee is, funnily enough, a street in Berlin) pops up more and more frequently, sitting nicely alongside “Silicon Roundabout” and “Silicon Forest” in the growing list of cities lucky enough to obtain their own version of California’s favorite tech metonym. Housing prices have risen more than 32 percent since 2007, and while the Wall Street Journal calls it a “melting pot of talent,” and that fine-art lecturer you’re sometimes forced to hang out with calls it “the place to be.” But not everyone is so excited.

Pro-hipster poster by the Hipster Antifa Neukölln group. The top line reads, “Gentrify our neighbourhood—more bars—more wifi—more organic markets.”

The anti-hipster rhetoric has become so prevalent these days that it’s even prompted pro-hipster advocacy groups to counteract some of the prejudice. (Is being anti-anti-hipster the new hipster?) Hipsters get so much of the blame because they’re what academics call “middle gentrifiers”—artistic types who flock to the cheap rent and subsequently make the area seem trendy to listings magazines who think that video-art installations in dirty squats equal cool, pushing up the rent and forcing out the established community (in this case, largely Turkish) who’ve lived there for years.

It’s the same story from Dalston to Neukölln, with exactly the same signifiers: kebabs and dance music are the face of 21st-century European gentrification.

A “not for sale” sign outside the Køpi 137 squat.

Unlike London, however, this is a city that values its mietrecht—its tenants’ rights—and it refuses to go down without a fight. Most people see gentrification as an unstoppable force, but Berlin might be the first city that actually has a chance to effectively challenge that preconception.

Two weeks before the first wall demo, 500 people gathered to protest the eviction of a family who couldn’t afford their rising rent. They left 15 cars burned and ten police injured. Similar protests have been happening almost every week for the past two months, and one this Tuesday got particularly violent. It’s difficult to pinpoint why more intense protests are kicking off now after years of increasing rent, but it’s safe to say that the backlash is getting visibly more violent.

The Køpi 137 squat remains in place, despite attempts by police to evict its residents.

On the frontline of the debate are the squatters. For a while, people thought they were doomed, but in a city where even senior citizens will squat their retirement home to prevent its closure, a blanket downfall of squatters seems unlikely.

Cuvry Brache is a “free space” that won the right to exist despite attempts to develop the area. People camp there in tents and hold festivals in the summer.

The squatters’ existence is a bit of a paradox. Those taking residence at Køpi 137 and the Cuvry Brache squat in the Kreuzberg district know that gentrification threatens their existence, but they also know that their existence encourages gentrification. The more radical squats that exist in Kreuzberg, the more appealing that Kreuzberg seems to middle-class art students and the developers that inevitably succeed them.

Their solution to this vicious circle of hipster-driven gentrification is to surround themselves with graffiti saying stuff like “No tourists, no hipsters, no yuppies, no photos” and chasing you with dogs if they see you pointing a camera toward them. In fact, the only way I managed to get photos was to go when the squatters were forced indoors by a foot of snow.

A teepee home at Cuvry Brache.

Those who aren’t squatting are protesting against the oncoming pileup of gentrification. I went to one demonstration held by residents of subsidised housing in Kottbusser Tor, an area in central Kreuzberg. Even though their accommodation is meant to be social housing, it’s becoming increasingly unaffordable.

“Every year we get a letter from our landlord raising the rent by 13 percent per square meter,” Matthias Clausen, one of the protest’s organizers, told me. “It’s like a countdown before we have to leave. That’s what gentrification feels like for my neighbors and me.”

Residents at Kottbusser Tor protesting their increasing rent. The sign reads, “Our neighbors are here to stay! Including those on benefits.”

Matthias continued: “We’re demonstrating because of the high rent that we can’t pay. We live in social housing, so our rent is subsidised and yet it’s still too much for our neighborhood, which is one of the poorest in Berlin.”

I asked him if many of his neighbors were being evicted. “Yes,” he responded. “Five or six letters of eviction are sent out every day in Berlin. We’ve managed to prevent many of them, though.

“New Berlin depends on the foundations of the old Berliners. Students and artists come here for the cheap rent, and that cultural avant garde destroys itself because they drive up prices. A lot of my friends feel bad for living here because they feel like they’re part of the problem, but it isn’t just an automatic process of the free market. There are individuals who are investing, who are driving up the rent, and there are ways around this. There are people making decisions and the process of decision making is something we can influence.”

More protests against increasing rent. The sign reads, “Stop racist exclusion! Not just in the real estate market!”

And Matthias has a point. Around half of Germany’s voters are renters, and with the federal elections coming up in September, politicians will be forced to address the issue. The Pankow district is already imposing a ban on luxury modernizations, while Peer Steinbrück, the Social Democrats’ candidate for chancellor, has proposed reviving Germany’s low-income housing program that was left behind in the 60s.

The destruction of the East Side Gallery might seem like a death knell for old Berlin, but that isn’t necessarily the case. The important thing is that so many people demonstrated against it, and that more and more protests are happening every month. As the issue starts to reach its boiling point, the world should keep its eyes fixed on Berlin because it may just provide the first real solution to the gentrification that’s been sidelining heritage and bulldozing history all around the world.

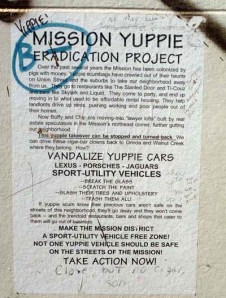

Eikon Investments, the firm that proposed a dot-com office remake for the Mission Armory, staged a party for the Internet business set, served by white-coated parking valets, and addressed by Da Mayor. Activists from MAC and the Digital Workers Alliance crashed the party.

Eikon Investments, the firm that proposed a dot-com office remake for the Mission Armory, staged a party for the Internet business set, served by white-coated parking valets, and addressed by Da Mayor. Activists from MAC and the Digital Workers Alliance crashed the party. The first influx of dot-com office development had been in the Northeast Mission Industrial Zone. The Bay View Bank Building was the first major incursion into the heart of the Mission — the Mission Street corridor. The Mission Street and 24th Street corridors are the main commercial and cultural heart of the Latino community in San Francisco, and many of the small businesses in these commercial strips are marginal. For example, produce markets are a common site in the Mission. A study of these markets by MEDA showed that only 16% had enough revenue to qualify for mortgage capital to buy their buildings. This puts them at the mercy of the current rental market. The incursion of high tech firms into this commercial district threatens to drive rents through the sky, as landlords drool at the prospect of much higher revenue per square foot.

The first influx of dot-com office development had been in the Northeast Mission Industrial Zone. The Bay View Bank Building was the first major incursion into the heart of the Mission — the Mission Street corridor. The Mission Street and 24th Street corridors are the main commercial and cultural heart of the Latino community in San Francisco, and many of the small businesses in these commercial strips are marginal. For example, produce markets are a common site in the Mission. A study of these markets by MEDA showed that only 16% had enough revenue to qualify for mortgage capital to buy their buildings. This puts them at the mercy of the current rental market. The incursion of high tech firms into this commercial district threatens to drive rents through the sky, as landlords drool at the prospect of much higher revenue per square foot.